anchorDesktop-grade apps

Modern websites are in many cases not really websites anymore, but in fact full blown apps with desktop-grade feature sets and user experiences that happen to run in a browser as opposed to standalone apps. While the much-loved Spacejam Website was a pretty standard page in terms of interactivity and design only about 2 decades ago

we can now go to Google Maps, zoom and rotate the earth in 3D space, measure distances between arbitrary points and have a look at our neighbor's backyard:

All of this functionality, interactivity and visual appeal comes at a cost though, mainly in the the form of JavaScript code. The median size of JavaScript used on pages across the Internet is now ca. 400KB on the desktop and ca. 360KB on mobile devices, an increase of ca. 36% and ca. 50% respectively over the past 3 years. All of this JavaScript not only has to be loaded via often spotty connections but also parsed, compiled and executed - often on mobile devices that are far less powerful than the average desktop or notebook computer (have a look at Addy Osmani's in-depth post on the matter for more details).

What all this leads to is that for many of these highly-interactive, feature-rich and shiny apps that are being built today, the first impression that users get is often this:

anchorSPAs

While JavaScript-heavy apps can be slow to start initially, the big benefit of the Single Page App approach is that once the application has started up in the browser, it is running continuously and handles route changes in the browser so that no subsequent page loads are necessary — SPAs trade a slow initial load for fast or often immediate subsequent route changes.

The initial response though that delivers the user's first impression will often be either empty or just a basic loading state as shown above. Only after the application's JavaScript has been loaded, parsed, compiled and executed, can the application start up and render anything meaningful on the screen. This results in relatively slow time to first meaningful paint (TTFMP) and time to interactive (TTI) metrics.

anchorTTFMP: Time to first meaningful paint

This is the time when the browser can first paint any meaningful content on the screen. While the time to first paint metric simply measures the first time anything is painted (which would be when the loading spinner is painted in the above example), for an SPA the time to first meaningful paint only occurs once the app has started and the actual UI is painted on the screen.

anchorTTI: Time to interactive

This is the time when the app is first usable and able to react to user inputs. In the above example of the SPA, time to interactive and time to first meaningful paint happen at the same time which is when the app has fully started up, has painted the UI on screen and is waiting for user input.

anchorThe App Shell Model

One popular approach for improving the startup experience of JavaScript-heavy applications is called the App Shell Model. The idea behind this concept is that instead of responding to the user's first request with an empty HTML document with only some script tags and maybe a loading spinner, the server would respond with the minimal set of code that is necessary for rendering the app's minimal UI and making it interactive. In most cases, that would be the visual framework of the app's main blocks and some barebones functionality associated to that (e.g. a working slideout menu without the individual menu items actually being functional).

Although this does not improve the app's TTFMP or TTI, at least it gives the user a first visual impression of what the app will look like once it has started up. Of course the app shell can be cached in the browser using a service worker so that for subsequent visits it can be served from that instantly.

anchorBack to SSR

The only really effective solution though for solving the problem of the meaningless initial UI - be it an empty page, a loading indicator or an app shell - is to leverage server-side rendering and respond with the full UI or something that's close to it for the initial request.

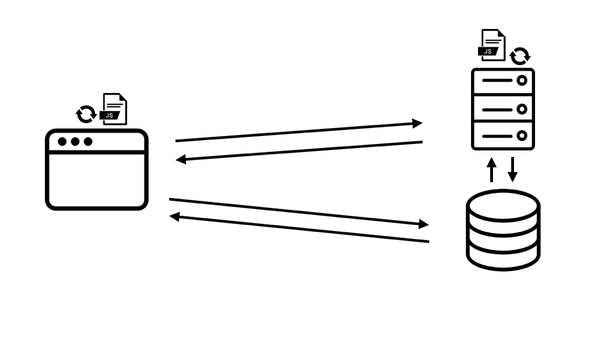

Of course it wouldn't be advisable to go back to classic server-side rendered websites completely, dropping all of the benefits that Single Page Apps come with (instance page transitions once the app has started, rich user interfaces that would be almost impossible to build with server side rendering, etc.) A better approach is to run the same single page app that is shipped to the browser on the server side as well as follows:

- the server responds to

GETrequests for all routes the single page app supports - once a request comes in, the server constructs an application state from the request path and potentially additional data like a session cookie and injects that into the app

- it then executes the app and renders the app's UI into a string, leveraging libraries like SimpleDOM or jsdom

- that string is then served as the response to the browser's initial request

- the pre-rendered response still contains all

<script>tags so that the browser would load and execute these scripts and start up the app in the browser as usual

With this setup, the TTFMP metric is dramatically improved. Although users still have to wait for the app's JavaScript to load and the app to start before they are able to use it, instead of only being shown a meaningless UI while they wait for that to happen, they see the app's full UI immediately as that is served in the response to the initial request. The initial UI can even be partly interactive - elements like links or even functional elements like hover menus that can be implemented in CSS only will already be usable before the app has started up.

anchorSPA + SSR + PWA

Combining SPAs with classic SSR, we get the best of both worlds - a fast TTFMP plus the benefits of an SPA like immediate page transitions, vivid UX etc. On top of that, patterns of PWAs can be added, for example caching the initial pre-rendered response in a service worker so that it can be shown immediately on subsequent visits or showing the app shell from the service worker cache and then injecting the SSR response into that which is likely available before the app has started up.

SPAs, SSR and PWAs are not orthogonal concepts that are exclusive of each other but are actually complementary. SSR can be leveraged for a fast TTFMP and some very basic functionality like links etc. Once the JavaScript referenced in the SSR response has been loaded, the SPA starts up in the browser, takes over the DOM and intercepts all subsequent route changes and handles them immediately in the browser. And finally concepts of PWAs like effective client-side caching and offline functionality via service workers can be added on top for maximal performance and the optimum user experience.

anchorDeployment

When leveraging SSR for SPAs, it is important to get some aspects of the deployment right. Pre-rendering the application for the first request is only an improvement over the classic way of serving an SPA and should not be a requirement to use the app. Neither should it slow down delivery of the app. To make sure these requirements are met, it is important to make sure of two things:

- The pre-rendering must run within a timeout so that if for some reason it takes longer than x ms or whatever a reasonable threshold for a particular app might be, the server cancels the pre-renderer and instead serves the SPA the classic way (which is responding with the static, empty HTML file).

- Likewise, errors in the pre-renderer should not be forwarded to the users and thus block them from booting the app in the browser. Whenever the pre-renderer encounters an error, it should fall back to serving the app the classic SPA way just like if it runs into the timeout.

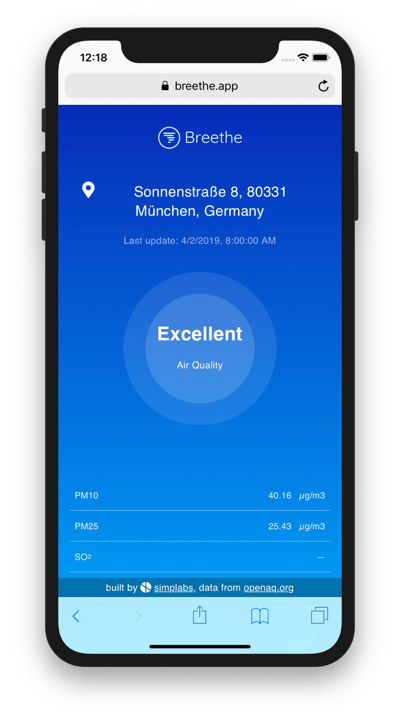

anchorBreethe

We implemented the patterns described in this post in Breethe, a PWA for accessing air quality data for locations around the world that we built as a tech showcase. Breethe is completely open source and available on github and we encourage everyone interested in the topic to check it out for reference.

anchorDrawbacks

Server-side-rendering an SPA comes with a drawback which is added latency. When serving an SPA as a static HTML file that contains only a loading state or an app shell, the HTML file can be served from a CDN which reduces latency. When serving the response for the initial request from a Node server, there will always be some additional latency. The Node server will likely not be running on an edge note in a CDN, thus connecting to it will take the user slightly longer than connecting to an edge node. Also, the server takes some time to run the app, capture what it renders and respond with that, adding further latency. Thus, the browser will know slightly later which scripts to load and thus start loading them slightly later which leads to a longer TTI.

However, with average TTI measurements in the range of several seconds for many sites in particular when requested from mobile devices, an added latency of a few hundred milliseconds might be well worth it in many cases. Without SSR, TTFMP is generally equal to TTI for SPAs and PWAs - with SSR, TTFMP occurs as soon as the initial response is received while TTI is only slightly delayed. So while the user needs to wait slightly longer for the app to be fully started up, the app's UI (and content) is available pretty much immediately. Whether that is a valuable improvement is a case-by-case decision of course. In the example of Breethe, when looking at the result page for a particular location, it's a pretty obvious decision:

While the user might need to wait for a few seconds (e.g. on a low performance mobile device with a spotty network connection) for the app to have fully started up and be interactive, the air quality data that they are interested in is available immediately.

anchorProgressive Enhancement

The possibilities of combining SPAs with SSR and PWA mechanics do not end with the above described patterns though but we can go a step further. As it turns out, leveraging SSR for an SPA enables to also leverage Progressive Enhancement patterns so that the initial response can be functional beyond just links and interactive elements built in CSS. Many things we're all doing in JavaScript in SPAs these days have equivalents in pure HTML. These might not be as powerful and elaborate as what can be done with modern JavaScript but they can serve as a fallback for when the app's JavaScript is slow to load or fails to load completely. That way we're coming back full circle to a concept from 1 or 2 decades ago where JavaScript enhances the HTML document rather than generating it - and all that while we're using an SPA that is completely written in JavaScript but that we're also running in the server side so that users don't necessarily have to wait until the app runs in their browsers.

I will elaborate on how exactly the approach works in the next post of this series so stay tuned!