anchorThe status quo

Let's start by getting an understanding of why things are the way they are. Chesterton would be proud…

Back in the days when computers were first created there were no package managers. There weren't even packages. Things were just being copied around and nobody had heard of "versions" yet.

At some point a few clever developers thought that it might be nice to share reusable pieces of code across applications and thus "packages" were born. One major downside of the early package infrastructure was that packages were shared across the operating system. That means, if you have two applications and both need a particular, but different, version of a package, you're essentially screwed.

Believe it or not, this is basically how everything in the Python and Ruby worlds work. These days there are ways to work around this and have an "environment" (with its packages) per project, but it is still quite hard to have multiple versions of the same package within such an environment.

When npm came around, they realized that this sort of thing wasn't very scalable and set out to fix this issue. Their main idea: instead of putting packages in some operating system folder the packages would be kept directly in the folder of each project. But also, each of the packages could also have other packages as dependencies within it. This is how the node_modules folder was born.

They formalized a rather simple algorithm to find the packages in the nearest node_modules folder: if you call require('chesterton') in a file, then it will look for a node_modules folder in the same folder as the file, and, if found, it will look for a chesterton folder inside it. If neither exists, it will look in the parent folder of the file for a node_modules/chesterton folder. And if that does not exist, it will look in the parent parent folder, and so on, and so on…

The beauty of this algorithm is that it allows us to have complicated dependency graphs:

our-app

├─ one-dependency@1.0.0

└─ another-dependency@3.0.1

└─ one-dependency@0.4.2

Don't get me wrong, I'm not saying complicated dependency graphs are necessarily a good thing, but in some cases they are hard to avoid. If necessary, I'd rather have two versions of the same dependency in a project, than not be able to use the dependency at all.

Anyway, that's how we got into this mess… Now let's see how we can get back out of it!

anchorPlug and maybe Play… sometimes

For years, the way npm did things was the established practice and any attempts of changing the status quo failed. With yarn, a new package manager was born that challenged a lot of things in the npm ecosystem… except for the node_modules structure. 😢

Well, that's not entirely correct. After years of development the yarn team finally came up with what they called "Plug'n'Play mode" (or "PnP" for short). This new mode promised us to share the dependencies across the whole machine while still allowing us to have multiple versions of the same package installed. 😍

Unfortunately, this new mode had one major downside: It monkey patched the require() function in Node.js, because it needed to essentially override the node_modules lookup algorithm. 😫

While this worked well in small, controlled environments, it eventually became clear that this was not a good long-term solution. There are still plenty of tools in the npm ecosystem that don't support this mode well, or even at all.

We need a different solution!

anchorThe shiny future

Remember the title of the blog post? One character to rule them all, one character to find them, … No, wait that was something different.

Ah, right, "one character saved 50 GB of disk space". That one character is… P.

It is the (first) P in pnpm. The simple solution: use pnpm install instead of npm install. Done!

If you're wondering "why P?", well, the P stands for performance.

But let me explain… pnpm managed to fulfil the promise that yarn made with its PnP mode, but without having to monkey patch anything. Instead, it is using hard links in a clever way, allowing the regular node_modules algorithm to work as intended, but still only having a single copy of each package version on the disk.

Fun fact: Did you notice how "PnP mode" starts with the letters pnpm? 😄

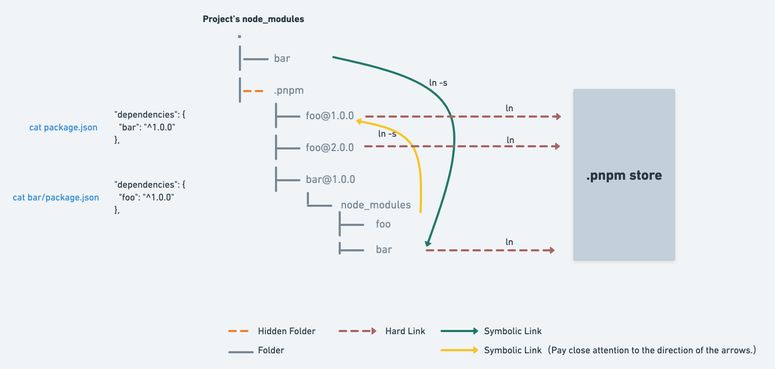

Twitter user xiaokedada has created a nice overview image on how pnpm creates its folder structure:

This might seem complicated at first, but it is relatively straight forward. On the right hand side, we have the global pnpm store, that contains all the packages and package versions that pnpm has downloaded to your machine. Each package version only exists exactly once in this store, and the node_modules folder in your projects are linking to this global store (dark red lines).

In the node_modules folder of our project we have a bar folder which points to the bar dependency of our project. However, there is also a hidden .pnpm folder which contains the real magic. Inside this folder are folders for every single package/version combination that is being used in your project.

This includes our own dependency bar in the bar@1.0.0 folder, but inside this node_module/.pnpm/bar@1.0.0 folder is not the dependency itself, but instead just another node_modules folder, with another bar folder inside of it, linking to the global pnpm store.

Whoa… that's complicated!

But there is a reason for this complicated folder layout. From the perspective of the bar package we will need access to the foo dependency, and we will need to access the correct version of it. That's why the node_modules/.pnpm/bar@1.0.0/node_modules/foo folder is just a link to the node_modules/.pnpm/foo@1.0.0/node_modules/foo folder, which itself links to the global pnpm store again.

tl;dr the complicated folder layout ensures that every package has access to its dependencies in the right version, but not anything else.

anchorConclusion

While pnpm has been around for quite a while, it has lately started to gain more momentum, with quite a few high profile projects migrating to it.

At Mainmatter we have started to convert a few of our own projects to it, and let me tell you that the 50 GB of saved disk space are not a joke. Some of us had dozens of individual Ember.js apps and addons installed, all using a roughly similar dependency tree. When you get to reduce all of these duplicated dependencies to just one copy per machine it quickly adds up.

While pnpm is certainly not without its issues either, it currently appears to be the least bad solution in the JavaScript ecosystem. We encourage you to try it out and message us if you hit any issues.

Finally, a huge thank you to the lead pnpm maintainer, Zoltan Kochan!