Rust has received a lot of developer attention and love ever since it entered the stage around a decade ago. And it's not only the developers that love the language – the decision makers at the big corporates agree Rust is a great technology to build on and the language has seen a lot of adoption throughout the industry over the past few years. AWS uses Rust heavily for their platform, Google uses it in Android, Microsoft uses it in Windows. Essentially, Rust is on track to replace C and C++ in many of the domains those were used before: systems programming, operating systems, all kinds of embedded systems, low level tooling, as well as in games and game engines.

Yet, we believe Rust has even more potential and a great future in other areas: the web and the cloud. Rust might not be an obvious choice there - those are not areas where many teams were previously using a low-level language like C or C++. Nonetheless, we believe that Rust can bring the development of web backends to the next level, giving teams access to capabilities that were previously out of reach – what those are we'll see in more detail below. We can already see quite a few companies using Rust successfully in the web and the cloud, even though Rust is still young and evolving in these areas: Truelayer, Discord, Temporal, Nando's, svix, Wingback, and many others.

anchorWhat?

Around 8 years after its 1.0 release, Rust is still a relative young ecosystem. Yet, it's reached a level of maturity that makes it a viable choice to build real applications and Rust's web ecosystem is no exception there. Rust is clearly ready for the web as arewewebyet.org confirms:

First of all, there's tokio, an asynchronous runtime that's a solid and performant foundation for networking applications. On top of that, there's mature and well-maintained web frameworks like axum and actix-web. There's mature drivers for all of the relevant datastores as well as ORMs. Finally, you can find libraries covering all other relevant aspects for building web apps, such as (de-)serialization, internationalisation, templating, observability, etc. Overall, Rust provides solid and stable building blocks for building ambitious web backends.

anchorWhy?

Of course one might ask: why should you care? What could motivate a team that already uses Ruby, Java, Elixir, TypeScript, Go, or whatever else, to adopt Rust? There are two key aspects that make Rust a great choice for building for the web:

- its efficiency and performance

- the reliability and maintainability gains brought by its type system

anchorEfficiency and Performance

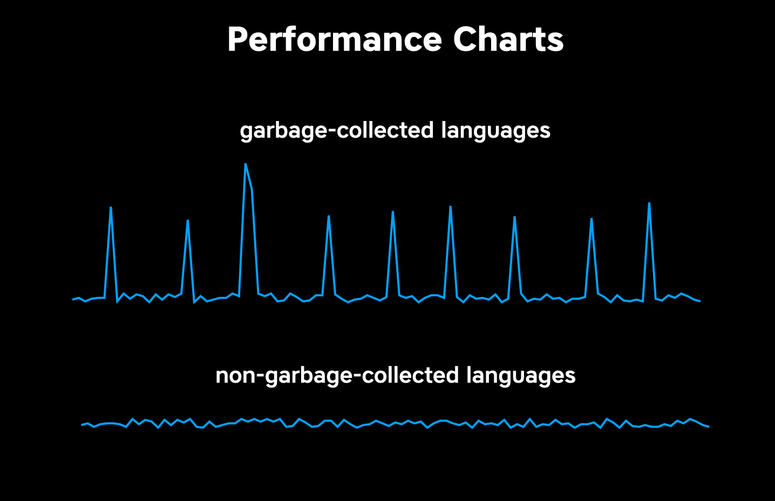

Rust is famously efficient and performant. It will easily outperform languages like JavaScript, Ruby, Python, etc. that are commonly used for web applications, by several orders of magnitude. Other languages may have a higher performance ceiling (e.g. Java or C# or Go), but you need to invest serious engineering effort to come close to the level of performance offered by Rust's toolkit out of the box. In addition, Rust has a key advantage: it doesn't bundle a garbage collector. Garbage-collected languages can be plenty fast, but they are not consistently performant at all times. The garbage collector will introduce pauses in order to free unused memory, negatively impacting the tail latency (p95/p99) of your applications. Rust doesn't have this problem: it can deliver consistent performance without those spikes.

C and C++ are the only other languages that allowed for such stable and consistent performance. Unfortunately, they are full of pitfalls and opportunities for shooting yourself in the foot, in particular by making mistakes doing manual memory management. As Linus Torvalds, the creator of Linux, says:

"[…] it is so close to the hardware that you can do anything with it. It is dangerous. It's like juggling chainsaws. I also see that it does have a lot of pitfalls and they're easy to overlook.

Linus Torvalds

Because of these dangers of C and C++, both languages are really only usable when you're an expert in them or have an expert team – if you don't, you end up with systems that will be unstable and full of security vulnerabilities. In the web field though, nobody has that expertise as everyone mostly uses very different languages like JavaScript, Python, Ruby, Elixir, etc. That way, Rust not coming with the same pitfalls, empowers developers to build software at levels of efficiency that were previously out of reach for them. Rust will typically outperform other technologies commonly used to build web backends by several orders of magnitude while at the same time keeping a significantly lower memory footprint.

Of course, if your Rust web server can respond to requests in a fraction of the time compared to other technologies, it also means it can respond to the same number of requests with a fraction of the servers, which again means a fraction of the hosting cost. That difference has real financial consequences – as great as cloud hosting is, it's certainly not cheap. Being able to just switch off a substantial amount of cloud servers can easily be a reduction of hundreds of thousands of Euros per month even for small to mid-sized products and companies.

[…] our Python services average about 50 req/s, NodeJS around 100 req/s, and Rust hits about 690 req/s. We can fit 4 Rust services on a k8 EKS node that would normally host a single Python service.

someone on reddit.com

Financial savings aren't even the whole story though. Using fewer servers also means using less energy. As good as running data centers on renewables is, the greenest energy still is the energy we don't use. And while it would be ridiculous to claim Rust is going to solve the climate crisis, it's important to acknowledge that the software we all write uses real resources and thus has an impact on the real world. Our industry has a tendency to forget about the resources our work consumes, although the ICT sector accounts for 8-10% of the European CO2 emissions – if we can use resource more efficiently and get the same output for less input, that's an aspect to consider when choosing a technology.

anchorReliability and Maintainability

While performance and efficiency might be the most obvious reasons to choose Rust for a project, they are not the only ones. Other, maybe more relevant reasons in many cases, are the reliability and maintainability gains that Rust's strong type system unlocks.

Snippets like this one are fairly typical for a web application (Ruby on Rails):

class User

attr :name

attr :active

attr :activation_date

def activate(activation_date)

self.active = true

self.activation_date = activation_date

save

end

def save

…

end

end

…

user.activate(Time.now)While this code is quite succinct and pleasant to read and writing code like this will let you reach your goal fast, there are problems. In this (admittedly simple) example, while we can see the user's attributes, we don't know what rules there might be around those (e.g., if active is true, activation_date must be set as well probably? If active is false, presumably activation_date should be nil?). In order to validate these assumption, one has to look into the implementation of the activate method which means relatively high effort is required to get to the information.

Looking at the invocation of the activate method, we can't know whether it might raise an error or what timezone we're supposed to pass the time in. And while Ruby might be a bit of an extreme example given its notorious flexibility, many of these problems can be found in other languages as well. Let's look at Java, as an example. We would still have no way to encode the rules around the active and activation_date attributes in the type system, nor when things can be null and we risk getting NullPointerExceptions at runtime.

These issues become more and more relevant over time as the codebase grows and the team working on it grows as well, or just changes as some people leave and others join. It is no longer true that everyone working on the codebase has a perfect mental model of the entire application and all the implicit assumptions being made throughout the codebase. Instead understanding those concepts will require people to carefully read through classes and methods and tests. That task becomes more and more unrealistic over time, in particular for new joiners of which there tend to be plenty in long living codebases over time. That not only decreases efficiency but also likely results in increased error rates in production as people not familiar with the application make mistakes.

The same code snippet as above but in Rust is much clearer and expressive:

enum User {

Inactive {

name: String,

},

Active {

name: String,

active: bool,

activation_date: DateTime<Utc>,

},

}

impl User {

fn activate(&self, activation_date: DateTime<Utc>) -> Result<(), DBError> {

match self {

User::Inactive { name } => {

let new_user = User::Active {

name: name.clone(),

active: true,

activation_date: activation_date,

};

new_user.save()

}

User::Active { .. } => Err(Error::default()),

}

}

fn save(&self) -> Result<(), DBError> {

…

}

}First of all, for the user model, we can use Rust's enum with associated data. That way, it's completely clear what inactive and active users look like and what attributes can be expected to be set in what scenarios – in fact, active and inactive users do not even have the same attributes but each only has the ones that make sense for the respective user state they represent. Also the attribute's types are clearly defined – not only is Rust typed while Ruby is untyped obviously but the types are also very precise so that e.g. for the activation_date field, the expected timezone is right in the type as well.

The signature of the activate function also encodes, explicitly, a lot of the information that was implicit in the Rails example. Again, the expected timezone for the activation_date is right in the type, and also the function returns Rust's Result which clearly communicates that errors might occur when calling it. In fact, the Rust compiler will require both the success and error variant of the Result to be handled so that no unhandled runtime exceptions can occur.

Additionally, the activation_date argument of the function is always guaranteed to have a value when the function is called since Rust does not have a concept of implicit nullability (as opposed to e.g. Java). If the activation_date could potentially not have a value at the place where its calculated, it would probably be an Option<DateTime<Utc>> which could not be passed to the activate function as its a different type than the expected DateTime<Utc>. The Rust compiler would only allow the code path for the Some variant of that Option to result in an invocation of the activate method so that activation_date is guaranteed to have a value when the function runs.

While this is obviously a rather simple example, it illustrates the two main advantages of Rust well:

- Many of the concepts and rules that were implicit in the Rails example are explicitly communicated through types in the Rust code. Active and inactive users can be clearly distinguished, and for the date fields even the expected timezone is encoded in the types. That expressiveness makes the code much more approachable, in particular to newcomers to the codebase, thus resulting in improved maintainability.

- Rust substantially improves reliability as well since whole classes of errors that are common in other languages (including typed languages such as Java or Go) will be detected at compile time instead of runtime. The compiler guarantees the

activation_dateargument of theactivatefunction to have a value and any error that's potentially returned by the function to be handled.

Overall, the improvements in reliability and maintainability that Rust comes with are often overlooked while everyone is focussed on Rust's performance. However, in many cases these benefits might be more relevant for a project's long term success than sheer performance numbers.

anchorHow & Where?

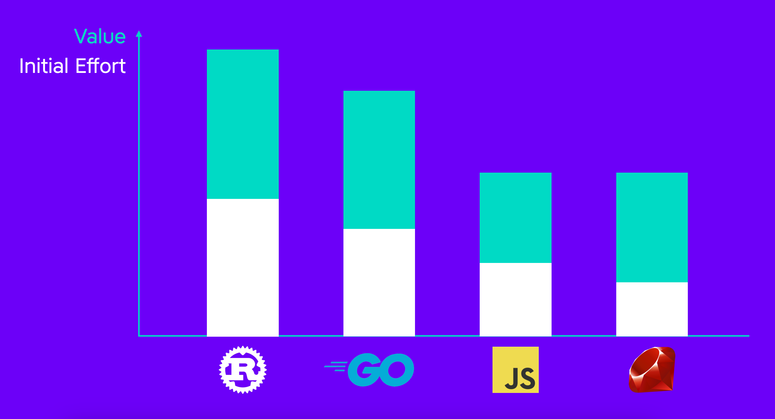

As Rust's main advantages are reliability, maintainability, efficiency, and performance, use cases for the language are obviously ones where these four aspects are particularly relevant. While one could say those aspects are always relevant and generally be correct saying that, the benefits come at a cost that needs to be accounted for.

Overall, Rust still requires a higher upfront investment than other technologies, in particular compared to those commonly used in web projects:

While languages like JavaScript and Ruby are made for getting results fast, Rust deliberately doesn't leave as much freedom and requires a program to pass all of the compiler's checks before one gets to a working result. That requires higher initial effort for building an application with Rust compared to those languages. Additionally, there's a mountain people need to climb before they're productive with Rust at all – that is mastering Rust's unique ownership system.

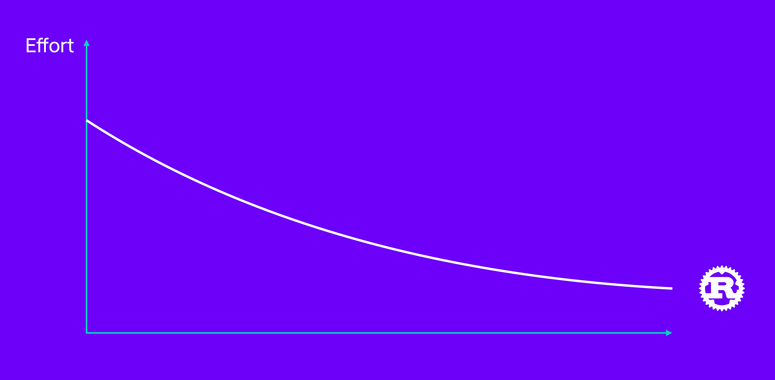

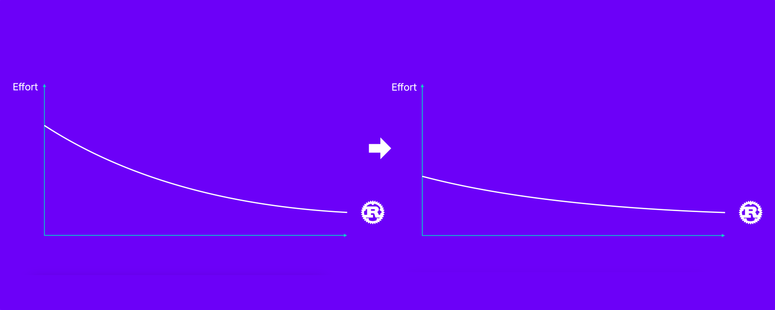

However, when looking beyond the initial stages of a project and expanding the view on a longer time horizon where aspects like maintainability, reliability, and stability become exceedingly important, the picture changes as the effort for working on Rust projects goes down over time:

Rust apps being more reliable and thus requiring less time invested into bug fixing, as well as being more maintainable and thus easier to work on efficiently with growing and changing teams, results in effort going down over time. That tends to be the other way round for other languages where effort goes up over time as the impact of reliability and maintainability challenges becomes bigger and more costly as the team grows. The additional investment made in the beginning when using Rust pays dividends over time.

anchorUse Cases & Adoption Paths

Based on Rust's strengths and effort curve, whenever evaluating whether or not to choose Rust for a particular case, the main questions to answer are:

- Does the team have Rust expertise already (and many teams that don't use Rust already actually have expertise because so many developers code in Rust in their freetime)?

- What are the requirements regarding reliability?

- What are the plans for long term maintenance?

- What scale is the system being built for and thus how much money could Rust potentially save in terms of hosting?

- Based on the answers to the above questions, is the additional initial investment worth it?

While in some cases the conclusion will be that the additional initial investment is not worth it, for some cases the assessment will be clearly in Rust's favor. Some typical use cases we're seeing include:

- For core business systems that implement the key business logic for a product, aspects like reliability and long-term maintainability are primary concerns.

- For financial systems, there is generally little tolerance for bugs and the improved stability that Rust leads to can be a deciding factor. Plus, performance is a key requirement with a clear financial impact in specific scenarios (e.g. trading systems).

- Any system that must be able to deliver high throughput and performance will clearly benefit from Rust. Systems like proxy servers that sit in front of a number of microservices must have minimal overhead and consistent performance. Garbage collected languages with their unreliable performance characteristics are typically not an option in these cases.

- Finally, for any system that is run at large scale, there are big saving potentials in terms of hosting costs.

Once a decision for Rust has been made, there's two main adoption paths – either an entire application is (re-)written from scratch in Rust or you are looking at incremental adoption alongside other technologies.

anchor(Re-)Starting Fresh

Whether an existing system is being replaced or something entirely new is being started, the Rust ecosystem is mature enough to build complete backends as explained above. While there might be no full-featured, batteries-included framework that handles all aspects of a big web backend application like a "Rust on Rails" just yet, all of the building blocks like web frameworks, ORMs, etc. exist and can be assembled together to cover all aspects that need to be handled in a full web backend.

One thing to keep in mind when starting a project from scratch: Rust isn't necessarily your friend for prototyping and explorative coding, the kind taking place when the project domain might not be fully understood and the team might not have a clear idea of the final architecture they are going for. While technologies like Ruby on Rails are specifically built for that kind of work but then show their shortcomings over time, Rust is the other way round, as mentioned before. The same mechanisms that lead to improved reliability and maintainability make it harder to experiment since Rust requires the entire codebase to be consistent at all times. Because of that, it may be easier to replace an existing system with a Rust implementation instead of starting from a blank slate.

anchorIncremental Adoption

While every engineer likes a greenfield project, incremental adoption paths are typically easier to manage. Instead of rewriting entire applications in Rust, it's usually much more straightforward to extract individual aspects of existing systems into Rust (micro) services. For these kinds of projects, the lack of full-featured macro frameworks is also less critical, as much of the aspects that such frameworks would cover might not be relevant for these projects at all due to their limited scope.

Overall, incremental adoption by (re-)implementing individual aspects of existing systems in Rust is the typical adoption path we're seeing. The reduced scope of such projects also reduces the overall risk – teams can evaluate whether Rust works for them without making a huge commitment. If they run into challenges working with Rust, no huge investment has been made and the decision is typically reversible without huge cost. If a team succeeds with Rust though, their success will typically inspire others and lead to more and more adoption throughout an organization.

An even easier adoption path than building (micro) services is writing native extensions in Rust. Teams that have existing Node/Ruby/Elixir/Python/etc. applications that might suffer from performance or stability issues, might choose to rewrite parts of those applications in Rust and directly integrate the Rust code with their existing applications as native extensions (to learn how that works in Elixir, have a look at Bart's post on the topic). While that used to require writing C or C++ code in most languages and thus wasn't a feasible option for most teams, Rust opens up that possibility. Like (micro) services, native extensions are a great first step on an incremental adoption path while keeping risk at a minimum.

anchorWhere to?

Rust is undoubtedly a great choice for building web applications in many cases. It offers significantly better efficiency and performance as well as improved reliability and maintainability compared to other technologies commonly used for building web applications. That increased value that Rust delivers comes at the cost of higher initial effort than for other technologies though. However, that doesn't have to stay like that forever and over time the initial effort required for adopting and building with Rust will go down, making it a viable choice for even more teams and projects.

The language itself will continue to evolve and become more approachable. At the same time, frameworks and libraries will also continue to evolve and improve their concepts and APIs, making them easier to use. The ease of use of libraries like e.g. express.js from the Node ecosystem is the benchmark that maintainers of web frameworks in Rust like Rob Ede, maintainer of actix, are aiming for. While an ambitious goal, it's actually one that's possible to reach in the mid future.

In parallel to existing frameworks and libraries like actix and axum continue to improve, new frameworks will be built at higher abstraction levels as well. As more teams adopt Rust for web backends, the community will explore and evaluate approaches, learn from evaluating those in different use cases, and collectively settle on a set of patterns and architectures. Eventually, we'll see full-featured macro-frameworks like a "Rust on Rails" that will significantly simplify building web applications in Rust.

And the future in which Rust is easier to approach and adopting it doesn't come at an additional initial cost, isn't so far away even. Google, who have been adopting Rust significantly for years, recently shared they don't really see a productivity penalty for Rust compared to any other language they use:

"Overall, we’ve seen no data to indicate that there is any productivity penalty for Rust relative to any other language these developers previously used at Google.

Lars Bergstrom, Google

While it might be questionable how that experience translates to other teams and companies, it is a strong positive signal for sure.

We at Mainmatter are highly optimistic that Rust will take off in the web and cloud space in the coming months and years and for that reason have made a strategic bet on Rust. We believe that Rust is the first step towards a new era of web development where developers can levarage a technology that allows them to reach higher and previously unthinkable levels of efficiency, stability, reliability, and maintainability without giving up on developer experience and productivity.